|

Author: Roger C. Alford

Source: BYTE, Jun 1990 Page 297+

HTMLized by Louis Ohland. Table conversion and style by Tomáš Slavotínek.

In the late 1970s, Al Shugart of Seagate Technology (then Shugart

Technology) developed the ST506 hard disk interface. In the spring of 1980,

Seagate introduced the 5-megabyte ST506 drive that became the namesake for the

interface. Several years later, Seagate introduced its 10-MB ST412 with

essentially the same interface.

The ST412's interface, however, included one additional feature that the

ST506 lacked buffered seeks. Most ST506 controllers and drives today support

the buffered seek option; they're commonly called ST506/412 devices.

The ST506 featured modified frequency modulation (MFM) data encoding and

could transfer data to and from the hard disk drive at 5 megabits per second.

With an eager and widening market at hand, the disk drive industry evolved

rapidly. Soon hard disks could handle 10-Mbps transfers, and several disk

drive, tape drive, and controller manufacturers saw the need for a faster

interface. They agreed that an enhanced, electrically compatible version of the

de facto standard ST506 interface made sense.

An ad hoc consortium formed, and the first working document for the new

interface the enhanced small disk interface appeared in May 1983. The enhanced

small tape interface followed, and in October of that year, the group decided

to merge the two interfaces into a single document, ESDI (enhanced small device

interface). The interface touted a 10-Mbps transfer rate, which is double that

of the ST506.

By 1985, optical disks were coming on strong, and a draft of the ESDI

specification that supported them appeared in March of that year. As industry

acceptance of ESDI continued to grow, it emerged as a potential American

National Standard. In January 1986, an ESDI steering committee formed, and the

Accredited Standards Committee X3T9.3 working group held its first meeting in

July of that year.

ESDI continued to find favor with manufacturers of high-performance hard

disk drives but didn't do as well in the tape industry. In May 1987, ESDI

proponents agreed to drop tape support from the proposed standard.

Early this year, ANSI finally adopted ESDI officially as ANSI X3.170-1990.

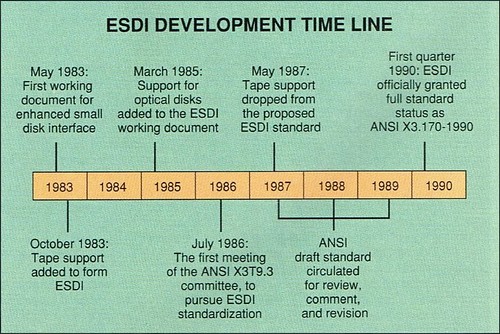

Figure 1 shows a time line for the development of ESDI.

Figure 1: ESDI Development Time Line

Seven years in the making, ESDI's ANSI certification finally came this year.

Two Standards: ESDI and SCSI

As ESDI developed and became a standard, so did another interface designed

to support high-speed disk drives and other peripherals ANSI's X3T9.2 committee

directed the standardization of SCSI. It became an official standard in 1986 as

ANSI X3.131-1986. A second generation specification, SCSI-2, is now nearing

completion.

SCSI often competes with ESDI for control of high-performance hard disk

drives in today's fast PCs. As I take a closer look at ESDI, I'll point out

some of the key comparisons between the two interfaces and try to clarify their

applications. (For a detailed look at SCSI, see Under the Hood in the February

and March BYTE.)

ESDI now finds wide acceptance in the PC marketplace. Manufacturers

including IBM, Compaq, and Dell use ESDI hard disk drive subsystems in their

high-performance machines. With Apple computers, of course, it's a different

story. Apple chose to make a SCSI connection standard equipment on the

Macintosh.

How ESDI Works

ESDI is a device-level interface. It connects directly to the hard disk

drive and controls basic operations, such as seek and head select. SCSI, in

contrast, is a system-level interface, or bus, that can connect to any of a

wide variety of devices simultaneously (including hard disk drives, scanners,

optical disks, printers, and tape drives) and can communicate with them by

means of highlevel commands. A SCSI hard disk drive needs intelligent SCSI

electronics and a device-level connection for controlling the disk. The latter

could, in theory, be an ESDI connection or something similar. Electrically and

mechanically, ESDI looks just like the ST506 interface. A common 34-conductor

control cable connects in daisy-chain fashion to all drives controlled by a

single controller. Each drive has its own 20-conductor data cable. Even the

popular four-pin power connector found on all standard PC floppy and hard disk

drives is defined as part of the ESDI standard.

While most of the ESDI signals are single-ended open-collector TTL (a single

wire referenced to a common ground), the clock and data signals are

differential (a complementary pair of wires, where only the voltage difference

between the wires is significant). That design maintains integrity even at very

fast data transfer rates. ESDI permits cable lengths of up to 3 meters (a

little over 9 feet).

Interface Signals

Table 1 shows the ESDI signal definitions for the 34-conductor and

20-conductor cables. I've included the ST506 signal definitions for comparison.

ESDI hard disk and optical disk connections work in slightly different ways;

I'll focus on hard disk applications.

|

34-Conductor Control Cable, ESDI

| Signal | Dir.

C/D | Sig.

pin | Gnd

pin |

|---|

| Head select 2(3) | → | 2 | 1 |

| Head select 2(2) | → | 4 | 3 |

| Write gate | → | 6 | 5 |

| Config/status data | ← | 8 | 7 |

| Transfer acknowledged | ← | 10 | 9 |

| Attention | ← | 12 | 11 |

| Head select 2(0) | → | 14 | 13 |

| Sector/address mark found | ← | 16 | 15 |

| Head select 2(1) | → | 18 | 17 |

| Index | ← | 20 | 19 |

| Ready | ← | 22 | 21 |

| Transfer request | → | 24 | 23 |

| Drive select 2(0) | → | 26 | 25 |

| Drive select 2(1) | → | 28 | 27 |

| Drive select 2(2) | → | 30 | 29 |

| Read gate | → | 32 | 31 |

| Command data | → | 34 | 33 |

|

34-Conductor Control Cable, ST506

| Signal | Dir.

C/D | Sig.

pin | Gnd

pin |

|---|

| Reserved | N/A | 2 | 1 |

| Head select 2 | → | 4 | 3 |

| Write gate | → | 6 | 5 |

| Seek complete | ← | 8 | 7 |

| Track 0 | ← | 10 | 9 |

| Write fault | ← | 12 | 11 |

| Head select 0 | → | 14 | 13 |

| (looped to pin 7 of data connector on disk) | | 16 | 15 |

| Head select 1 | → | 18 | 17 |

| Index | ← | 20 | 19 |

| Ready | ← | 22 | 21 |

| Step | → | 24 | 23 |

| Drive select 1 | → | 26 | 25 |

| Drive select 2 | → | 28 | 27 |

| Drive select 3 | → | 30 | 29 |

| Drive select 4 | → | 32 | 31 |

| Direction in | → | 34 | 33 |

|

|

20-Conductor Data Cable, ESDI

| Signal | Dir.

C/D | Sig.

pin | Gnd

pin |

|---|

| Drive selected | ← | 1 | N/A |

| Sector/address mark found | ← | 2 | N/A |

| Command complete | ← | 3 | N/A |

| Address mark enable | → | 4 | 5 |

| +Write dock | → | 7 | 6 |

| -Write clock | → | 8 | 9 |

| +Read/reference clock | ← | 10 | N/A |

| -Read/reference clock | ← | 11 | 12 |

| +Write data | → | 13 | N/A |

| -Write data | → | 14 | 15 |

| +Read data | ← | 17 | 16 |

| -Read data | ← | 18 | 19 |

| Index | ← | 20 | N/A |

|

20-Conductor Data Cable, ST506

| Signal | Dir.

C/D | Sig.

pin | Gnd

pin |

|---|

| Drive selected | ← | 1 | 2 |

| Reserved | N/A | 3 | 4 |

| Reserved | N/A | 5 | 6 |

| (to pin 16 of control connector on disk) | N/A | 7 | 8 |

| Reserved | N/A | 9 | |

| Reserved | N/A | 10 | 11 |

| +Write data | → | 13 | 12 |

| -Write data | → | 14 | 15 |

| +Read data | ← | 17 | 16 |

| -Read data | ← | 18 | 19,20 |

|

Table 1: Signal Definitions For ESDI And ST506

ESDI and ST506 use the same connectors. However, ESDI's high-level command

orientation differs markedly from that of the older ST506 interface (N/A=not

applicable).Head and drive selection bits appear in parentheses.

Signal directions: → from controller to disk; ← from disk to

controller.

An ESDI controller can accommodate as many as seven drives, although ESDI

controllers used in PCs typically support just two. Three drive-select signals

determine the active drive, in a binary fashion. When all three drive-select

signals are unasserted (low), no drive is selected.

Four head-select signals pick one of up to 16 heads on the active drive.

What if your drive has more than 16 heads? That's handled by means of the

Select Head Group command. When the drive reaches its operating speed, it sends

a ready signal to the controller. It also sends the index signal, the rising

edge of which indicates the beginning of each track. The index signal, which

pulses once per revolution of the platters, also appears on the data cable.

The function of the sector/address mark found signal varies depending on

whether the disk incorporates hard sectoring or soft sectoring. With hard

sectoring, drive electronics determine a fixed number of sectors per track. The

drive pulses the sector/address mark found line at the start of each sector.

You don't find many hard-sectored disks these days I can't think of any offhand

but, nevertheless, ESDI supports them.

With soft sectoring, the disk's operating software determines the number of

sectors per track. Address marks codes placed on the platter before the sector

data delineate sectors. When the drive detects a mark, it pulses sector/address

mark found.

Finally, the read gate signal enables the selected read/write head for a

read operation, and write gate sets up a write operation.

On the data cable, the drive-selected signal tells the controller that there

is indeed one, and only one, drive at the specified drive-select address. And

the address mark enable signal tells a softsectored drive to write an address

mark at the current position of the selected read/write head. Utility programs

can use this signal, valid only when write gate is asserted, to change the

number of sectors per track.

Moving the Data

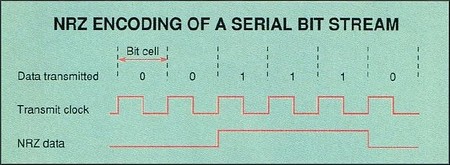

Figure 2: NRZ Encoding Of A Serial Bit Stream

To distinguish bits in NRZ data, you need a separate source of clock

information.

Four differential (or balanced) signals affect data transfer between the

controller and the hard disk: write data, read data, write clock, and

read/reference clock. Data transfer requires both clock and data signals. The

clock signal indicates when the data signal is valid. Typically, the rising

edge of each clock cycle indicates the start of a new data bit in a serial data

stream. In its purest form, data and clock are physically separate signals;

this scheme is called NRZ (nonreturn-to-zero) encoding. Figure 2 illustrates

NRZ encoding of a serial bit stream.

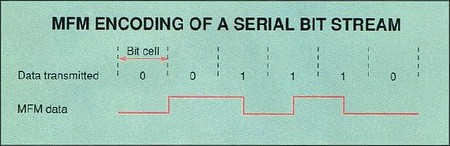

Figure 3: MFM Encoding Of A Serial Bit Stream

MFM encoding (like RLL encoding) merges data and clock information

into a single, combined signal.

But to store data on a hard disk platter, you've got to combine the data and

clock signals. Encoding methods that can do that include FM, MFM, and run

length limited (RLL). Figure 3 illustrates MFM encoding. If there's a

transition at the center of a bit cell, the bit is a binary one; otherwise,

it's a zero. Transitions also occur at the beginning of each zerobit cell that

is preceded by another zerobit cell.

It's reasonably straightforward to encode these various formats when writing

to the disk but a lot harder to decode them when reading the disk. A special

circuit called a data separator does the job. It incorporates a phase-locked

loop circuit to synchronize with and lock onto the clock as it's recovered from

the encoded signal. For reliable data and clock separation, the encoded signal

has to be free of electrical noise.

The basic ST506 interface transfers data between the controller and the hard

disk drive in MFM format at 5 Mbps. For several years now, ST506 controllers

and drives have also been available that use RLL encoding instead of MFM. That

buys a 50 percent increase in the data transfer rate to 7.5 Mbps and also

boosts storage capacity by 50 percent. RLL encoding is more complex than MFM

and requires a more advanced data separator. Nevertheless, most new drives use

it.

Since the ST506 controller transfers encoded information to and from the

drive, the data separator has to reside on the controller. The developers of

ESDI realized that encoded data sent over long cables might not transfer

reliably at 10 Mbps. So ESDI transfers NRZ data between the controller and the

hard disk drive and uses separate, balanced data and clock signals. The hard

disk drive itself has to encode the data before storing it on its platters, and

it must also incorporate a data separator to decode the data.

This approach makes the drives attached to an ESDI controller more complex

and more costly than ones used in an ST506 subsystem. And each drive needs its

own data separator; there's no way to share a single, controller-resident

separator. But the benefits outweigh the drawbacks. The scheme ensures superior

data integrity, and the encoding scheme no longer depends on the controller. An

ESDI hard disk drive can use one of several flavors of RLL encoding, or even

MFM encoding. (I don't know of any ESDI drives that use MFM, but it's

possible.) It's even possible to mix encoding methods within a multidrive ESDI

subsystem.

Decoded data shows up on the data cable as the read data signal. The

read/reference clock signal, which the hard disk drive generates, controls the

timing of both read and write operations. When read gate is active,

read/reference clock acts as the read clock, carrying the clock signal that the

data separator extracts from the stored clock/data information. When there's no

read in progress, the hard disk drive generates a reference clock signal on the

read/reference clock line.

The controller uses the write data signal to present NRZ data to the hard

disk drive. The write clock signal derived from the hard disk drive 's

reference clock provides the timing clock for the write data signal. Note that

the hard disk drive controls both the read and write data transfer rates it

must, since it has control over its own data encoding scheme.

The Serial Command Mode

Five signals on the control cable and one on the data cable communicate

commands and status information between the controller and the drive:

config/status data, transfer acknowledged, attention, transfer request, command

data, and command complete. The controller sends 17-bit command-plus-parity

words to the controller serially. It places each bit on the command data line,

asserts the transfer request handshake signal to the hard disk drive, and

awaits the transfer acknowledged return handshake signal from the hard disk

drive. Configuration and status information returns to the controller in a

similar fashion.

Two other signals figure importantly in ESDI's serial command mode:

attention and command complete. The hard disk drive asserts attention when it

wants the controller to request its standard status. That's generally a

response to a fault condition on the hard disk. Writing to the hard disk can't

occur while attention is asserted.

Command complete is the only serial mode signal on the data cable. The hard

disk drive generates it. When unasserted, it tells the controller that the

drive can't respond to the interface typically, because the drive is trying to

recover from an error or is performing another internal function.

Commanding the Drive

ESDI defines 12 commands for use with hard disk drives, as shown in table 2.

Just five are mandatory. The high-order 4 bits of the 16-bit command word

determine the command type; the low-order 12 bits can contain supplemental

command information. The commands also include a trailing parity bit.

Command

Number

(bits 15-12) |

Command Definition |

Command

Modifier

(bits 11-8) |

Command

Subscript

(bits 7-0) |

Command

Parameter

(bits 11-0) |

| 0000 (0) | Seek | No | No | Yes |

| 0001 (1) | Recalibrate | No | No | No |

| 0010 (2) | Request Status | Yes | Yes | No |

| 0011 (3) | Request Configuration | Yes | Yes | No |

| 0100 (4) | Select Head Group* | No | No | Yes |

| 0101 (5) | Control | Yes | No | No |

| 0110 (6) | Data Strobe Offset* | Yes | No | No |

| 0111 (7) | Track Offset* | Yes | No | No |

| 1000 (8) | Initiate Diagnostics* | No | No | Yes |

| 1001 (9) | Set Bytes per Sector* | No | No | Yes |

| 1010 (10) | Set High Order Value* | Yes | No | Yes |

| 1011 (11) | Reserved | No | No | No |

| 1100 (12) | Reserved | No | No | No |

| 1101 (13) | Reserved | No | No | No |

| 1110 (14) | Set Configuration* | Yes | Yes | No |

| 1111 (15) | Reserved | No | No | No |

Table 2: ESDI Serial-Mode Commands

The 16-bit command word includes a 4-bit command identifier (bits 15-12),

and it can also include modifier, subscript, and parameter values (bits 11-0).

* optional commands

Seek causes the drive to seek to the cylinder specified by the

low-order 12 bits of the command word. Recalibrate sends the heads to

cylinder zero and restores the drive's data strobe offset and track offset

values to zero. Request Status solicits 16 bits of standard or vendor

specific status information, based on the command modifier bits.

Request Configuration can solicit the drive's transfer rate, number

of heads, number of cylinders, hard/soft sectoring information, and much more.

The Control command resets certain functions (including the interface

attention after a fault), and it can also optionally implement spindle on/off

control commands. (I suppose this would be helpful if you're using an ESDI

drive in a laptop.)

Optional Commands

Select Head Group supports drives with more than 16 heads. A 4-bit

value selects one of 16 head groups, each of which contains 16 heads. Data

Strobe Offset and Track Offset address specific regions of the

disk; data recovery utilities can use these commands. Initiate

Diagnostics tells the hard disk drive to run its internal diagnostics, if

any.

Set Bytes per Sector works with hard-sectored disks; it can adjust

the number of bytes stored in each sector. Set Configuration has

several applications. It can, for example, set varying transfer rates for

different cylinders of the disk, on hard disk drives that support zone

recording. It can also support hard disk drives that change angular velocity

(rotational speed) at different cylinder ranges to maintain a relatively

constant linear velocity.

Putting ESDI to Work

ESDI has capacity to spare. A single ESDI hard disk drive can hold a

terabyte of data. Even if you stick to the 512-byte sectors that DOS and OS/2

prefer, the limit is a healthy 137 gigabytes. And, of course, it's fast. Most

ESDI drives today transfer at 10 Mbps, but 15-Mbps drives have started to

appear. And the theoretical limit, 24 Mbps, leaves plenty of room for further

performance improvements.

ESDI expects a 1-to-1 interleave; it would make little sense to operate such

a high-performance interface any other way. While some recent ST506 interface

implementations can now also operate at a 1-to-1 interleave on high-performance

PCs, the data transfer rate of these interfaces still restricts the overall

performance potential of the hard disk drive subsystem.

If you're familiar with the ST506 interface, you'll find connecting an ESDI

hard disk drive to its controller virtually identical. The controller will have

a 34-pin header connector for the control cable, and the hard disk drive will

have a 34-contact card-edge connector to mate with the ribbon cable. Similarly,

the controller will have a 20-pin header connector for each hard disk drive it

supports (typically two), into which you will plug the 20-conductor data cable.

And the hard disk drive will have a 20-contact card edge connector that also

mates with the 20-conductor cable. Both card-edge connector on the ESDI hard

disk drive must have a key slot, per the ESDI standard, and any good drive

cables should incorporate the key to keep the cables from being connected to

the drive incorrectly. The ESDI drive will also accept the standard four-pin PC

power connector.

Standard ST506/MFM hard disk drives are formatted for 17 sectors per track.

The higher density and higher data transfer rate of ST506/RLL hard disk drives

require the number of sectors per track to increase to 26. With most current

ESDI hard disk drives in the PC marketplace operating at 10 Mbps, these drives

are typically formatted for 32 to 35 sectors per track; most use 34 or 35.

The Software Environment

How compatible is ESDI with your software? That depends. If you inhabit the

DOS world exclusively, all ESDI controllers for PCs will work acceptably. Some

have their own BIOS-level driver. Others take great pains to emulate the ST506

interface found on IBM's original AT system. That means the interface can work

with the hard disk driver that is already resident in the system's ROM

BIOS.

If you want to use an ESDI subsystem under OS/2 or Xenix, things aren't

quite so automatic. A WD 1003-compatible controller should work acceptably, but

controllers with their own driver could have a problem. If you buy IBM's ESDI

hard disk drive subsystem, you can rest assured it will work with IBM's OS/2.

Similarly, Dell's ESDI subsystem will work with that company's version of OS/2.

When in doubt, verify compatibility with the distributor or manufacturer of the

ESDI controller before buying.

You'll also want to make sure that your ESDI controller will operate

properly with the drive you select. There have been cases of drive/controller

incompatibilities. Although the recent standardization of the ESDI connection

has alleviated much of the concern, some ESDI hard disk drives implement

special, optional functions; these require matching controllers. To avoid

potential mix-and-match incompatibility problems, you can purchase an ESDI hard

disk drive subsystem, including the controller and cables.

ESDI vs. SCSI

While SCSI's parallel bus implementation differs from ESDI's serial transfer

approach, both interfaces support highspeed data transfers and require the hard

disk drive to incorporate some intelligence. SCSI requires more intelligence,

however, and entails more overhead. For this reason, ESDI subsystems often

outperform similar SCSI subsystems in overall effective data transfer rate.

SCSI, however, holds an ace. A SCSI drive can accept a command, disconnect

from the bus while processing it, and then reconnect to the host controller.

That way, multiple SCSI drives can process commands or transfer data

concurrently. Network controllers and multiuser systems that can apply this

feature will undoubtedly embrace SCSI.

ESDI will continue to grow in popularity, probably at least into the

mid-1990s. SCSI will also gain ground. As software standards develop that

permit more-uniform use of SCSI controllers with a wide variety of peripherals

(e.g., hard disk drives, optical disks, and scanners), it seems likely that

SCSI will eventually become the dominant high-performance hard disk drive

interface in the PC world. But for now, ESDI thrives. With practically

unlimited capacity, plenty of room for performance gains, and an ANSI seal of

approval, ESDI and fast PCs will march together for years to come.

Roger C. Alford is a computer design engineer and a freelance

writer.

|